In the last post we took a look at the RabbitMQ clustering feature for fault tolerance and high availability. In this post we'll dig deep into Apache Kafka and its offering.

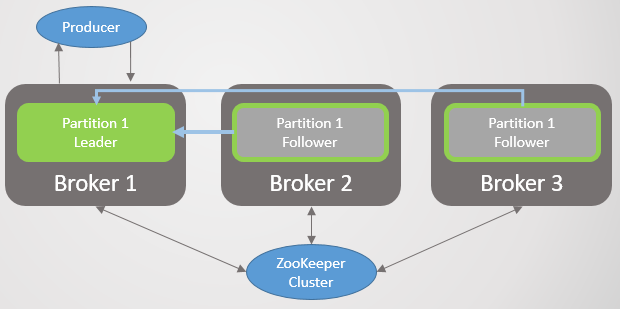

With Kafka the unit of replication is the partition. Each topic has one or more partitions and each partition has a leader and zero or more followers. When you create a topic you specify the number of partitions and the replication factor. A replication factor of three is common, this equates to one leader and two followers. Both leaders and followers can be referred to as replicas.

Fig 1. Four partitions distributed across three brokers.

All reads and writes on a partition go to the leader. Followers periodically send fetch requests to the leader to get the latest messages. Consumers do not consume from followers, the followers only exist for redundancy and fail-over.

Partition Fail-Over

When a broker dies, it will likely be the host of multiple partition leaders. For each partition that has lost a leader, a follower on a remaining node will be promoted to leader. In fact this isn't always the case as it depends on whether there are followers that are "in-sync" with the leader, and if not, whether fail-over to an out-of-sync replica is allowed. But for now let's keep it simple.

When Broker 3 dies, a new leader on broker 2 is elected for partition 2.

Fig 2. Broker 3 dies and the partition 2 follower on broker 2 is elected the new partition leader.

Then when broker 1 dies, partition 1 loses its leader and it fails-over to broker 2.

Fig 3. One broker left. All leaders on a single broker with zero redundancy.

When Broker 1 comes back online it adds four followers giving some redundancy to each partition. But the leaders remain concentrated on broker 2.

Fig 4. Leaders remain on broker 2.

When broker 3 comes back we are back to three replicas per partition. But still all leaders are hosted on broker 2.

Fig 5. Unbalanced leaders after recovery of broker 1 and 3.

Kafka gives us better tooling for rebalancing leaders than RabbitMQ. With RabbitMQ we had to rely on an unsupported plug-in or a script that used policy changes to migrate the master node at the cost of reduced redundancy during the migration. Also, for large queues, we would have had to accept unavailability during synchronization.

Kafka has the concept of preferred replica leaders. When Kafka creates the partitions of a topic, it tries to distribute the leaders of each partition evenly across the nodes and marks those first leaders as the preferred leaders. Over time, due to server restarts, server failures and network partitions, the leaders might end up on different nodes to the preferred replica. Just like in the more extreme case above.

To fix that Kafka offers two options:

The topic configuration auto.leader.rebalance.enable=true which allows the controller node to reassign leadership back to the preferred replica leaders and thereby restore even distribution.

An administrator can use the kafka-preferred-replica-election.sh script to perform it manually.

Fig 6. Replica leaders rebalanced

That was the simplistic version of partition leader fail-over, it's a good place to start but the reality is more complex though still relatively simple. It all comes down to the In-Sync Replicas (ISR).

In-Sync Replicas (ISR)

The ISR is the set of replicas of a partition that is considered "in-sync". The ISR will always contain the leader (while there are surviving replicas) and zero or more followers. A follower is considered "in-sync" if they have been completely up-to-date with the leader at some point within the replica.lag.time.max.ms time period. Being up-to-date with the leader means having an exact copy of the messages of the leader.

A follower will be removed from the ISR if:

they have not made a fetch request within the replica.lag.time.max.ms time period (they are assumed dead)

they have been out of date for longer than the replica.lag.time.max.ms time period (they are a slow follower)

Followers make fetch requests at the replica.fetch.wait.max.ms interval which by default is 500ms.

In order to clearly explain the purpose of the ISR we need to look at producer acknowledgements and go through some fail-over scenarios. Producers can choose when a broker sends an acknowledgement:

acks=0, no acknowledgement is sent (fire and forget)

acks=1, an acknowledgement is sent once the leader has written the message to its local log

acks=all, an acknowledgement is sent once all replicas in the ISR have written the message to their local log.

In Kafka terminology, a message is committed once the ISR has persisted a message. Acks=all is the safest option though can introduce extra latency. We'll go through two fail-over examples and see how the "acks" producer config interacts with the ISR concept.

Acks=1 and the ISR

In this example we'll see that when the leader does not wait for followers to persist each message then we are likely to see message loss in a leader fail-over. Fail-over to an out-of-sync follower can be permitted or disallowed with the unclean.leader.election.enable configuration.

In this example our producer uses acks=1. Our partition is distributed across all three brokers. Broker 3 is lagging, it was last up-to-date with the leader 8 seconds ago and currently 7456 messages behind. Broker 1 is more up-to-date being only a second out of date. Our producer sends a message and gets an ack back quickly, with 0ms added due to any slow or dead followers because the leader does not wait for them.

Fig 7. ISR has three replicas.

The broker 2 dies and the producer gets a connection error. Meanwhile leadership fails-over to broker 1 losing 123 messages. The follower on broker 1 was in the ISR but not fully up-to-date with the leader when it failed.

Fig 8. Fail-over loses messages.

The producer has multiple brokers in its bootstrap.servers producer config and is able to ask another broker who the new partition leader is. It makes a connection to broker 1 and continues to send messages.

Fig 9. Message sending resumes after brief interruption

Broker 3 falls further behind. It is making fetch requests but it cannot keep up. This could be due to a slow network link between the brokers, a storage issue etc. It is removed from the ISR. The ISR now consists of a single replica, the leader! The producer continues to send messages and getting acks.

Fig 10. Broker 3 follower removed from ISR.

Broker 1 fails and leadership fails-over to broker 3 losing 15286 messages! The producer gets a connection error. The fail-over to a follower outside of the ISR was only possible because of the unclean.leader.election.enable=true setting. If it were set to false then the fail-over would not have happened and all reads and writes would be refused. In this case we'd need to bring back broker 1 with its data intact so it could resume leadership.

Fig 11. Broker 1 dies. Fail-over loses a large number of messages.

The broker establishes a connection to the last broker and sees that this broker is now the leader of partition 0. It starts sending its messages to broker 3.

Fig 12. After brief interuption, message again being sent to partition 0.

We saw that except for brief interuptions while the producer established new connections and discovered the new leader, messages were getting sent throughout the scenario. This configuration produces availability at the cost of consistency (data safety). Kafka lost thousands of acknolwedged messages but was able to continue accepting writes throughout.

Acks=all and the ISR

Let's replay that scenario again, but with acks=all. Broker 3 is averaging 4 seconds of lag. Our producer sends a message with acks=all but does not receive a quick response this time. The leader must wait for all replicas in the ISR to have persisted the message.

Fig 13. ISR has three replicas. One replica is slow, adding latency to writes.

After 4 seconds of added latency, broker 2 is able to send an ack to the producer. All replicas are fully up-to-date now.

Fig 14. All replicas persist the message and an ack is sent.

Broker 3 falls further behind now and is removed from the ISR. Latency is now greatly reduced as the ISR has no slow replicas. Broker 2 only has to wait for broker 1 to get the message and broker 1 is averaging 500ms of lag.

Fig 15. Replica on Broker 3 is removed from the ISR.

Then broker 2 dies and leadership fails over to broker 1 without message loss.

Fig 16. Broker 2 fails.

The producer discovers the new leader and starts sending messages to it. Latency is further reduced because now the ISR consists of a single replica! So although the producer says acks=all, if the ISR is one replica then it adds no extra redundancy.

Fig 17. The replica on broker 1 takes over leadership without message loss.

Then broker 1 dies and leadership fails-over to broker 3 losing 14238 messages!

Fig 18. Broker 1 dies and the unclean fail-over produces messive data loss.

We could have chosen to not set the unclean.leader.election.enable setting to true. By default it is false. Using acks=all with unclean.leader.election.enable=true gives us availability with some extra data safety. But as you can see, we can still lose messages.

But what if we want more data safety? We could make sure unclean.leader.election.enable = false, but that is not necessarily going to protect us against data loss. If the lost leader failed hard, data included, then messages are still lost, plus we get unavailability until an admin recovers the situation.

A better way would be to guarantee redundancy of all messages or refuse writes. If we refuse to accept a message if it is not redundantly stored, then at least from the broker's perspective, we are making data loss require two or more simultaneous failures.

Acks=all, min.insync.replicas and the ISR

With the min.insync.replicas topic config, we can turn up data safety a notch. Let's go through the last part of that scenario again, but this time with min.insync.replicas=2.

So broker 2 has the replica leader and the follower on broker 3 has been removed from the ISR.

Fig 19. ISR of two.

Broker 2 dies and leadership fails-over to broker 1 without message loss. But now the ISR consists of only one replica. This falls short of the minimum number in order to receive writes and so the broker responds to writes with a NotEnoughReplicas error.

Fig 20. ISR of one lower than min.insync.replicas

This configuration chooses consistency over availability. We guarantee that each message is written to least two replicas before acknowledging them. This gives much greater confidence to our producer. In this example, in order to lose messages we'd need two replicas get lost before the message could be replicated to an additional follower which is unlikely. But if you want to be super paranoid you could set your replication factor to 5 and your min.insync.replicas to 3. You would need three brokers to go down simultaneously to lose an acknowledged write! Of course you'll be paying for the additional latency though.

When Availability Is Necessary For Data Safety

Just like with RabbitMQ, sometimes being available is necessary for data safety. You need to think about:

Can my publisher simply return an error upstream and the upstream service or user can retry later?

Can my publisher persist the message locally or to a database so it can retry later?

If the answer is no then optimizing for availability may end up being better for data safety. Either way you will end up losing data but you may lose less data optimizing for availability than refusing writes. So it is a balancing act and the decision depends on your situation.

The Purpose of the ISR

The ISR exists to balance data safety with latency. It allows for a majority of replicas to fail and still provide availability while minimising the impact of dead or slow replicas in terms of latency.

We can turn the replica.lag.time.max.ms setting to our needs. It is basically saying how much latency we are willing to accept when using acks=all. The default is ten seconds. If you decide that ten seconds is too long then you could reduce it. That will increase the frequency of changes to the ISR as followers are removed and added again however.

RabbitMQ simply has a set of mirrors that must be replicated to. Slow mirrors can introduce longer latencies and dead mirrors can take up to the net tick time period to be detected. The ISR is an interesting way to avoid those higher latency issues. The risk of the ISR is that it can remove redundancy as the ISR can shrink to just the leader. If you want to avoid those situations then you can use the min.insync.replicas topic config to control that.

Ensuring Client Connectivity

Clients can be given multiple brokers that they can connect to, in the bootstrap.servers producer and consumer configs. The idea is that even if one node goes down, the client has multiple nodes it knows about and can open a connection to them. The bootstrap servers might not be the leaders of the partitions the client needs, instead the boostrap servers are a bridgehead. The client can ask them which node hosts the leader of the partition they want to read/write to.

With RabbitMQ, clients can connect to any node and internal routing ensures that the client talks to the right node. This means you can put a load balancer in front of RabbitMQ. Kafka requires clients to connect to the node that hosts the leader of the partition they need to work with. So a load balancer will not work. The bootstrap.servers is critical for ensuring that clients can talk to the right nodes and find the new node once a fail-over has occurred.

The Kafka Consensus Architecture

So far we haven't covered how a cluster can know when a broker has failed, or how leadership election occurs. In order to cover how Kafka deals with network partitions first we'll need to understand Kafka's consensus architecture.

Each cluster of Kafka nodes is deployed alongside a Zookeeper cluster. Zookeeper is a distributed consensus service that allows a distributed system to attain consensus around some given state. It is distributed itself and is has chosen consistency over availability. A majority of Zookeeper nodes are required in order to accept reads and writes.

Zookeeper is responsible for storing state about the Kafka cluster:

The list of topics, the partitions, configuration, current leader replicas, preferred replicas.

The cluster members. Each broker sends a heartbeat to the Zookeeper cluster, when Zookeeper fails to receive a heartbeat after period of time Zookeeper assumes the broker has failed or otherwise unavailable.

Electing the controller node which includes controller node fail-over when the controller dies.

The controller node is one of the Kafka brokers which has the responsibility of electing replica leaders. Zookeeper sends the Controller notifications about cluster membership and topic changes and the Controller must act on those changes.

For example, when a new topic is created with 10 partitions and a replication factor of three. The controller must elect one leader per partition, trying to distribute the leaders optimally across the brokers.

For each partition it:

updates Zookeeper with the ISR and leader

sends a LeaderAndISRCommand to each broker that hosts a replica of that partition, informing the brokers of the ISR and leader.

When a Kafka broker dies that hosts a replica leader, Zookeeper sends a notification to the Controller and it will elect a new leader. Again, the Controller updates Zookeeper first, then sends a command to each hosting broker notifying them of the leadership change.

Each leader is responsible for maintaining the ISR. It uses the replica.lag.time.max.ms to determine membership of the ISR. When the ISR changes, the leader updates Zookeeper of the change.

Zookeeper is always updated of any change in state so that in the case of a fail-over, that the new leader can smoothly transition into leadership.

Fig 21. Kafka consensus

The Replication Protocol

Undertstanding the details of replication helps us understand potential data loss scenarios better.

Fetch requests, Log End Offset (LEO) and the Highwater Mark (HW)

We have covered that followers are periodically sending fetch requests to the leader. The default interval is 500ms. This differs from RabbitMQ in that with RabbitMQ, the replication is not initiated by the queue mirror but by the master. The master pushes changes to the mirrors.

The leader and each follower stores a Log End Offset (LEO) and Highwater Mark (HW). The LEO is the last message offset the replica has locally and the HW is the last committed offset. Remember that to be committed, a message must have been persisted to each replica in the ISR. That means that the LEO is likely a little ahead of the HW.

When the leader receives a message, it persists it locally. A follower makes a fetch request, sending its own LEO. The leader then sends a batch of messages starting from that LEO and also sends the current HW. When the leader knows that all replicas have persisted a message at a given offset, it advances the HW. Only the leader is able to advance the HW and it lets the followers all know the current value in the fetch responses. This means that the followers may be lagging behind the leader regarding the messages but also regarding knowing the current HW. Consumers are only delivered messages up to the current HW.

Note that "persisted" means written to memory, not disk. For performance, Kafka fsyncs to disk on an interval. RabbitMQ also writes to disk periodically, but the difference is that RabbitMQ will only send a publisher confirm once the master and all mirrors have written the message to disk. Kafka has made the decision to acknowledge once a message is in memory for performance reasons. Kafka is making the bet that redundancy will make up for the risk of storing acknowledged messages in memory only for a short period of time.

Leader Fail-Over

When a leader fails, the Controller is notified by Zookeeper and elects a new leader replica. The new leader will make the new HW its current LEO. The followers will then be informed of the new leader. Depending on the version of Kafka, each follower will:

truncate its local log to the HW it knows about and makes a fetch request to the new leader from that offset

make a request to the leader to know the HW at the time of it’s election to leader, then truncate its log to that offset. Then start making periodic fetch requests, starting at the offset.

The reason that a follower partition may need to truncate its log after leader election is that:

When a leader fail-over occurs, the first follower in the ISR to register itself to Zookeeper wins the leader election and becomes the leader. Each follower in the ISR, while being "in-sync" may or may not be fully caught up with the former leader. It is possible that the follower that gets elected is not the most caught up. Kafka ensures that there is no divergence between replicas. So to avoid divergence, each follower must truncate to the HW of the new leader at the time of its election. This is another reason why acks=all is so important if you must have consistency.

Messages are written to disk periodically. If all nodes of a cluster failed simultaneously, different replicas will have persisted to disk up to a different offset. It is entirely possible that when the brokers come back online again, the new leader that gets elected could be behind its followers because it made its last fsync further in the past than its peers.

Rejoining a cluster

Just like with leader fail-over, replicas that rejoin a cluster discover who the leader replica is and truncate their log to their HW (at the time of their election). RabbitMQ treats new nodes and existing nodes that rejoin in the same way. Both are treated as completely new nodes and if a broker has any existing state, it throws it away. If automatic synchronization is used then the master must replicate all its current contents to the new mirror in a "stop the world" manner. The master cannot receive any reads or writes during this period. This "discard all my data and stop the world while I get replicated all messages" approach is problematic for large queues.

Kafka is a distributed log and in general will store more messages than a queue like RabbitMQ. With RabbitMQ, reading the data removes it from the queue. Active queues should hopefully stay relatively small. But Kafka is a log and stores messages according to its data retention policy which could be days or weeks of messages. This "stop the world" approach to synchronization is totaly unacceptable for a distributed log. Instead, Kafka followers simply truncate their log to the leader’s HW (at the time of its election) in the event that their copy is ahead of the leader. In the more likely case that the follower is behind the leader, they simply start making fetch requests, starting from their current LEO.

New or rejoined followers will start outside of the ISR and not participate in message commits. They will simply be there, fetching messages as fast as they can until they are caught up with the leader and are added to the ISR. There is no blocking, there is no throwing away all their data.

Network Partitions

Kafka has more moving parts than RabbitMQ and so has a more complex set of behaviours when a cluster suffers a network partition. But Kafka was built from day one to run as a cluster and is well thought out when it comes to network partitions.

Below are a few different network partition scenarios:

Scenario 1: A follower cannot see the leader, but can still see Zookeeper

Scenario 2: A leader cannot see any of its followers, but can still see Zookeeper

Scenario 3: A follower can see the leader, but cannot see Zookeeper

Scenario 4: A leader can see its followers, but cannot see Zookeeper

Scenario 5: A follower is completely partitioned from both the other Kafka nodes and Zookeeper

Scenario 6: A leader is completely partitioned from both the other Kafka nodes and Zookeeper

Scenario 7: The Kafka controller node cannot see another Kafka node

Scenario 8: The Kafka controller cannot see Zookeeper

Each of the above will exhibit different behaviours.

Scenario 1: A follower cannot see the leader, but can still see Zookeeper

Fig 22. Scenario 1: ISR consists of three replicas.

A network partition separates broker 3 from brokers 1 and 2, but not from Zookeeper. Broker 3 is no longer able to send fetch requests and after replica.lag.time.max.ms is removed from the ISR and does not contribute to message commits. As soon as the partition is resolved it will resume fetch requests and rejoin the ISR when caught up with the leader. Zookeeper will continue to receive heartbeats throughout and will assume the broker to be alive and well throughout.

Fig 23. Scenario 1: Broker removed from the ISR after passing replica.lag.time.max.ms without a fetch request.

There is no split brain or paused node like with RabbitMQ, instead it suffers reduced redundancy.

Scenario 2: A leader cannot see any of its followers, but can still see Zookeeper

Fig 24. Scenario 2: Leader and two followers

The network partition separates the leader partition from its followers, but the broker can still see Zookeeper. Just like with Scenario 1, the ISR shrinks but this time it shrinks to only the leader as the followers all cease sending fetch requests. Again, there is no split-brain. Instead there is a loss of redundancy for new messages until the partition is resolved. Zookeeper will continue to receive heartbeats throughout and will assume the broker to be alive and well throughout.

Fig 24. Scenario 2: ISR shrunk to only the leader

Scenario 3: A follower can see the leader, but cannot see Zookeeper

A follower is partitioned from Zookeeper but not from the broker with the leader. The result is that the follower continues to make fetch requests and continues to be a member of the ISR. Zookeeper will no longer receive heartbeats and will assume the broker to be dead, but as it is only a follower there are no recupercussions.

Fig 25. Scenario 3: Follower continues to send fetch requests to the leader

Scenario 4: A leader can see its followers, but cannot see Zookeeper

Fig 26. Scenario 4: Leader and two followers

The leader is partitioned from Zookeeper but not from the brokers with the followers.

Fig 27. Scenario 4: Leader isolated from Zookeeper.

After a short while Zookeeper will mark the broker as dead and notify the Controller. The Controller will elect a follower as the new leader. However the original leader will continue to think it is the leader and will continue to accept writes with acks=1. The followers will no longer be sending fetch requests to the original leader and so the original leader will presume them dead and attempt to shrink the ISR to itself. But because it has no connectivity to Zookeeper it won’t be able to and at that point it will refuse more writes.

Acks=all messages will not be acknowledged because at first the ISR includes all replicas, but they will not acknowledge receipt of the messages. When the original leader attempts to remove them from the ISR it will fail to do so and stop accepting any messages at all.

Clients soon detect the leadership change and start writing to the new leader. Once the network partition is resolved the original leader will see that it is no longer the leader and will truncate its log to the HW that the new leader had when the fail-over occurred. This is to avoid divergence of their logs. It will then start sending fetch requests to the new leader. Any writes in the original leader that had not been replicated to the new leader are lost. That is, the messages acknowledged by the original leader during those seconds when there were two leaders, will be lost.

Fig 28. Scenario 4. The leader on Broker 1 becomes a follower after the network partition is resolved.

Scenario 5: A follower is completely partitioned from both the other Kafka nodes and Zookeeper

A follower is completely isolated from both its peer Kafka brokers and Zookeeper. It will simply be removed the ISR until the network partition is resolved and it can catch up again.

Fig 29. Scenario 5: The isolated follower is removed from the ISR.

Scenario 6: A leader is completely partitioned from both the other Kafka nodes and Zookeeper

Fig 30. Scenario 6: A leader and two followers

A leader is completely isolated from its followers, the Controller and from Zookeeper. It will continue to accept writes with acks=1 for a short period.

Fig 31. Scenario 6: The leader becomes isolated from other Kafka nodes and Zookeeper

After replica.lag.time.max.ms has passed without fetch requests it will try to shrink the ISR to itself but will be unable to do so as it cannot talk to Zookeeper and it will stop accepting writes.

Meanwhile, Zookeeper will have marked the isolated broker as dead and the Controller node will have elected a new leader.

Fig 32. Scenario 6: Two leaders

The original leader may accept writes for a few seconds but then stop accepting any messages. Clients update themselves every 60 seconds with the latest meta data. They will be informed of the leader change and start writing to the new leader.

Fig 33. Scenario 6. Producers switch over to the new leader

Any acknowledged writes made to the original leader since the network partition began will be lost. Once the network partition is resolved the original leader will discover it is no longer the leader via Zookeeper. It will then truncate its log to the HW of the new leader at the time of the election and start fetch requests as a follower.

Fig 34. Scenario 6: The original leader becomes a follower after the network partition is resolved.

This is a case where a partition can be in split-brain for a short period, though only if acks=1 and min.insync.replicas is 1. The split-brain is automatically ended either when the network partition is resolved and the original leader realizes it is no longer the leader, or all clients realize the leader has changed and start writing to the new leader - whichever happens first. Either way, some message loss will occur but only with acks=1.

There is also a variant of this scenario where just before the network partition, the followers fell behind and the leader shrunk the ISR to itself. Then the network partition isolates the leader. A new leader is elected but the original leader continues to accept writes, even acks=all because the ISR is already only itself. These writes will be lost when the network partition is resolved. So to avoid this variant the only solution is to use min.insync.replicas = 2.

Scenario 7: The Kafka controller node cannot see another Kafka node

In general, the result of the Controller being isolated from another Kafka node is that it will not be able to communicate any leadership changes to that node. At worst, this can cause short-term split-brain situations like in scenario 6. More commonly it will simply result in a broker not being a candidate for leadership in a fail-over.

Scenario 8: The Kafka controller cannot see Zookeeper

The Controller is isolated from Zookeeper. Zookeeper will mark the broker as dead due to lack of heartbeats and a new Kafka node will be elected Controller. The original controller may continue to think that it is the controller but because it cannot receive any notifications from Zookeeper it will have no actions to perform. Once the partition is resolved it will realize it is no longer the Controller and be just a normal Kafka node.

Scenarios Conclusions

We see that network partitions that affect followers do not result in message loss, just reduced redundancy for the duration of the network partition. This of course can lead to data loss if one or more nodes are lost.

Network partitions that isolate leaders from Zookeeper can end up with message loss for messages with acks=1. Not being able to see Zookeeper causes short duration split-brains where we have two leaders. The remedy for this is to use acks=all.

Also min.insync.replicas being two or more adds extra guarantees that such short-term scenarios do not cause message loss, like with the scenario 6 variant.

Message Loss Recap

Let's list the ways in which you can lose data with Kafka:

Any leader fail-over where messages were acknowledged with acks=1

Any unclean fail-over (to a follower outside of the ISR), even with acks=all

A leader isolated from Zookeeper receiving messages with acks=1

A fully isolated leader whose ISR was already shrunk to itself, receving any message, even acks=all. This is true only if min.insync.replicas=1.

Simultaneous failures of all nodes of a partition. Because messages are acknowledged once in memory, some messages may not yet have been written to disk. When the nodes come back up some messages may have been lost.

Unclean fail-overs can be avoided by either disabling them or ensuring that redundancy is always at least two. The most durable configuration is a combination of acks=all and min.insync.replicas greater than 1.

RabbitMQ vs Kafka Durability/HA Round-Up

Both offer a primary-secondary replication solution for durability and high availability. However, RabbitMQ has an achilles heel. Rejoining nodes discard their data and synchronization is blocking. This double whammy makes durability of large queues very problematic with RabbitMQ. You either have to accept reduced redundancy or accept long periods of unavailability. The reduced redundancy increases the risk of massive data loss. But if queues can remain small, then short periods of unavailability (a few seconds) to ensure redundancy can be dealt with via connection retries.

Kafka does not share this problem. Kafka only discards data from the point where the leader and follower are already diverging. All shared data is kept. Also, replication is non-blocking. The leader can continue to accept writes while the new follower is catching up. This makes joining or rejoining a cluster a trivial problem for the administrators. There are still headaches of course, such as network bandwidth used for replication. If multiple followers are added all at the same time the network can reach capacity.

RabbitMQ does have some durability advantage when it comes to simultaneous failures of a cluster. RabbitMQ will only send a publisher confirm when a message has been written to disk on the master and all mirrors. But this adds extra latency for two reasons:

fsyncs are invoked every few hundred milliseconds

mirrors can go offline and it can take up to the net tick time to discover it is down. This can add latency when a mirror is slow or down.

Kafka takes the gamble that if a message is stored on multiple nodes, then it is safe to acknowledge the messages once they are in memory. This exposes Kafka to message loss of any type of acknowledged write (even acks=all, min.insync.replicas=2) in the event of simultaneous failure.

Overall Kafka has been proven to handle large message volumes and was built for scale. With its tunable consistency you can turn durability up to 11 if you need to. Replication factor of five with min.insync.replicas of three will make message loss a very rare event. If your network can take that kind of replication factor and you can afford the price tag of that level of redundancy then that option is open to you.

RabbitMQ clustering is a good option as long as you don't have very large queues. Even small queues can get big quick if they are high velocity. Once your queues get big then you start needing to make hard decisions about availability vs durability. RabbitMQ clustering is best suited for use-cases that are not massive scale, where the flexibility benefits of RabbitMQ outweigh any downsides of its clustering design.

One antidote to RabbitMQ's weakness regarding large queues is to break up your large queues into many smaller ones. If you don't require total ordering of the entire queue but only ordering of related messages (messages of a given customer for example) orno ordering at all, then check out my early stage Rebalanser project that allows you to partition a queue into multiple smaller ones.

Lastly, don't forget there have been multiple bugs in both RabbitMQ and Kafka regarding their clustering and replication. Over time the systems have become more mature and stable but no message is ever 100% safe! Also datacenter wide disasters do happen!

If I have missed anything out, made a mistake or you disagree with any of my opinions feel free to add a comment or contact me.

I don't know if this is the end of the series as there are still plenty more things to talk about. I haven't written an opinion post with a round-up of the entire series. I get asked a lot "Should I choose Kafka or RabbitMQ?", "Which one is better?". The truth is that it really depends on your use-case, current expertise etc. I am hesitate to write an opinion piece as it would likely be too simplistic to give both systems justice for all the use-cases and constraints out there. I have written this series so you can form your own opinion.

What I will say is that they are both leaders in this space. Due to my own personal experience, the types of projects I have been involved with, things like message ordering guarantees and reliability are high up in my mind when it comes to messaging and that bias may have come out in this series. I see other up and coming technologies that lack those durability and message ordering guarantees, then I look at RabbitMQ and Kafka and see the tremendous value they both offer.

Thanks for reading!