Object storage is taking over more of the data stack, but low-latency systems still need separate hot-data storage. Storage unification is about presenting these heterogeneous storage systems and formats as one coherent resource. Not one storage system and storage format to rule them all, but virtualizing them into a single logical view.

The primary use case for this unification is stitching real-time and historical data together under one abstraction. We see such unification in various data systems:

Tiered storage in event streaming systems such as Apache Kafka and Pulsar

HTAP databases such as SingleStore and TiDB

Real-time analytics databases such as Apache Pinot, Druid and Clickhouse

The next frontier in this unification are lakehouses, where real-time data is combined with historical lakehouse data. Over time we will see greater and greater lakehouse integration with lower latency data systems.

In this post, I create a high-level conceptual framework for understanding the different building blocks that data systems can use for storage unification, and what kinds of trade-offs are involved. I’ll cover seven key considerations when evaluating design approaches. I’m doing this because I want to talk in the future about how different real-world systems do storage unification and I want to use a common set of terms that I will define in this post.

From my opening paragraph, the word “virtualizing” may jump out at you, and that is where we’ll start.

Data Virtualization

I posit that the primary concept behind storage unification is virtualization. Virtualization in software refers to the creation of an abstraction layer that separates logical resources from their physical implementation. The abstraction may allow one physical resource to appear as multiple logical resources, or multiple physical resources to appear as a single logical resource. We can use the term storage virtualization and data virtualization though for me personally I find the difference too nuanced for this post. I will use the term data virtualization.

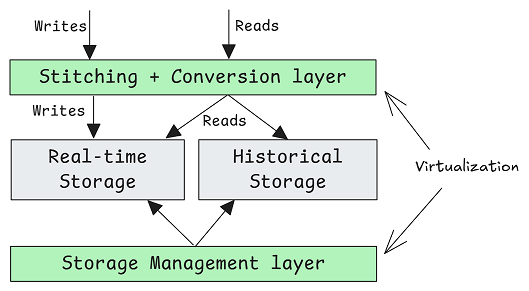

A virtualization layer can present a simple, unified API that stitches together different physical storage systems and formats behind the scenes. For example, the data may exist across filesystems with a row-based format and object storage in a columnar format, but the application layer sees one unified logical model.

Data virtualization is the combination of:

Frontend abstraction: Stitching together the different physical storage into one logical model.

Backend work: Physical storage management (tiering, materialization, lifecycle management).

Let’s dig into each in some more detail.

Physical storage management

How data is written and managed across these different storage mediums and formats is a key part of the data virtualization puzzle. This management includes:

Data organization / format

Data tiering

Data materialization

Data lifecycle

“Data organization” is about how data is optimized for specific access patterns. Data could be stored in a row-based format, a graph-based format, a columnar format, and so on. Sometimes we might choose to store the same data in multiple formats in order to efficiently serve different query semantics (lookup, graph, analytics, changelogs). That is, we balance trade-offs between access semantics and the cost of writes, the cost of storage and the cost of reads. Trade-off optimization is a key part of system design.

“Tiering” is about moving data from one storage tier (and possibly storage format) to another, such that both tiers are readable by the source system and data is only durably stored in one tier. While the system may use caches, only one tier is the source of truth for any given data item. Usually, storage cost is the main driver. In the next subsection, I’ll describe how there are two types of tiering: Internal vs Shared.

“Materialization” is about making data of a primary system available to a secondary system, by copying data from the primary storage system (and format) to the secondary storage system, such that both data copies are maintained (albeit with different formats). The second copy is not readable from the source system as its purpose is to feed another data system. Copying data to a lakehouse for access by various analytics engines is a prime example.

“Data lifecycle management” governs concerns such as data lifetime and data compatibility. Tiering implies lifecycle-linked storage tiers where the canonical data is deleted in the source tier once copied to the new tier (move semantics). Materialization implies much weaker lifecycle management, with no corresponding deletion after copy. Data can be stored with or without copies, in different storage systems and different formats, but the logical schema of the data may evolve over time. Therefore compatibility is a major lifecycle management concern, not only across storage formats but also across time.

Internal Tiering, Shared Tiering and Materialization

We can classify tiering into two types:

Internal Tiering is data tiering where only the primary data system (or its clients) can access the various storage tiers. For example, Kafka tiered storage is internal tiering. These internal storage tiers as a whole form the primary storage.

Shared Tiering is data tiering where one or more data tiers is shared between multiple systems. The result is a tiering-materialization hybrid, serving both purposes. Tiering to a lakehouse is an example of shared tiering.

Internal tiering is the classic tiering that we all know today. The emergence of lakehouse tiering is relatively new and is a form of shared tiering. But with sharing comes shared responsibility. Once tiered data is in shared storage, it serves as the canonical data source for multiple systems, which adds an extra layer of discipline, control and coordination.

7 Considerations for Data Virtualization (aka storage unification)

1. The Challenges of Shared Tiering

Shared tiering is a kind of hybrid between internal tiering and materialization. It serves two purposes:

Tiering: Store historical data in a cheaper storage.

Materialization: Make the data available to a secondary system, using the secondary system’s data format.

A key aspect of shared tiering is the need for bidirectional lossless conversion between “primary protocol + format” and “secondary protocol + format”. Getting this part right is critical as the majority of the primary system’s data will be stored in the secondary system’s format.

The main driver for shared tiering is avoiding data duplication to minimize storage costs. But while storage costs can be lowered, shared tiering also comes with some challenges due to it serving two purposes:

Lifecycle management. Unlike materialization, the data written to the secondary system remains tied to the primary. They are lifecycle-linked and therefore data management should remain with the primary system. Imagine shared tiering where a Kafka topic operated by a Kafka vendor tiers to a Delta table managed by Databricks. Who controls the retention policy of the Kafka topic? How do we ensure that table maintenance by Databricks doesn’t break the ability of the tiering logic to read back historical data?

Schema management. Schema evolution of the primary format (such as Avro or Protobuf) may not match the schema evolution of the secondary format (such as Apache Iceberg). Therefore, great care must be taken when converting from the primary to the secondary format, and back again. With multiple primary formats and multiple secondary formats, plus changing schemas over time, the work of ensuring long-term bidirectional compatibility should not be underestimated.

Exposing data. Tiering requires bidirectional lossless conversion between the primary and secondary formats. When tiering to an Iceberg table, we must include all the metadata of the source system, headers, and all data fields. If there is sensitive data that we don’t want to be written to the secondary system, then materialization might be better.

Fidelity. Great care must be taken to ensure that the bidirectional lossless conversion between formats does not lose fidelity.

Security/encryption. End-to-end encryption will of course make shared tiering impossible. But there may be other related encryption related challenges, such as exposing encryption metadata in the secondary system.

Performance overhead. There may be a large conversion cost when serving lagging or catch-up consumers from secondary storage, due to the conversion from the secondary format to the primary.

Performance optimization. The shared tier serves two masters and here data organization can really make the difference in terms of performance and efficiency. But what can benefit the secondary can penalize the primary and vice versa. An example might be Z-order compaction in a lakehouse table, where files may be reorganized (rewritten) changing data locality such that data will be grouped into data files according to common predicates. For example, compacting by date and by country (when where clauses and joins frequently use those columns). While this reorganization can vastly improve lakehouse performance, it can make reads by the primary system fantastically inefficient compared to internal tiering.

Risk. Once data is tiered, it becomes the one canonical source. Should any silent conversion issue occur when translating from the primary format to the secondary format, then there is no recourse. Taking Kafka as an example, topics can have Avro, Protobuf, JSON among other formats. The secondary format could be an open table format such as Iceberg, Delta, Hudi or Paimon. Data files could be Avro, Parquet or ORC. With so many combinations of primary->secondary->primary format conversions, there is some unavoidable additional risk associated with shared tiering. Internal tiering is comparatively simple, you tier data in its primary format. In the case of Kafka, you tier log segment files directly.

While zero-copy shared tiering sounds attractive, there are practical implications that must be considered. I am sure that shared tiering can be made to work, but with great care and only if the secondary storage remains under the ownership and maintenance of the primary system.

Note: The risks of fidelity and compatibility issues can be mitigated by storing the original bytes alongside the converted columns, but this introduces data duplication which many proponents of shared tiering are advocating against.

I wrote about data platform composability, enabled by the open-table formats. The main premise is that we can surface the same physical tabular data in two platforms. One platform acts as the primary, writing to the table and performing table management. Secondary platforms surface that table to their own users as a read-only table. That way, we can compose data platforms while ensuring table ownership and management responsibility remain clear.

This same approach works for shared tiering. The primary system should have full ownership (and management responsibility) of the lakehouse tiered data, making it a purely readonly resource for secondary systems. In my opinion, this is the only sane way to do shared lakehouse tiering, but it adds the burden of lakehouse management to the primary system.

2. Client vs server-side stitching

Where does the work of stitching different storage sources live? Should it exist server-side, or is it better as a client-side abstraction?

One option is to place that stitching and conversion logic server-side, on a cluster of nodes that serve the API requests from clients. This is the current choice of:

Kafka API compatible systems. Kafka clients expect brokers to serve a seamless byte stream from a single logical log, so Kafka brokers do the work of stitching disk-bound log segments with object-store-bound log segments.

HTAP and real-time analytics databases.

Another option is to place that stitching logic client-side, inside the client library. Through some kind of signalling or coordination mechanism the client must know how to stitch data from two or more storage systems, possibly using different storage formats. The client must house the data conversion logic to surface the data in the logical model. If this is a database API, then the client will also have to perform the query logic, and hopefully is able to push down some of the work to the various storage sources.

Client-side stitching can make sense if the client sits above two separate high-level APIs, such as a stream processor above Kafka and a lakehouse.

But it’s also possible to place stitching client-side within a single data system protocol. The benefit of client-side stitching is that we unburden the storage cluster from this work. For example, it would be possible to make Kafka clients download remote log segments instead of the Kafka brokers being responsible, freeing brokers from the load generated by lagging consumers.

On the downside, putting the stitching and conversion client-side makes clients more complicated and can make concepts such as storage format evolution and compatibility more difficult. A lot depends on what kind of control the operator has over the clients. If clients are tightly controlled and kept in-sync with the storage systems and their evolution, then client-side stitching might be feasible. If however, clients are not managed carefully and many different client versions are in production, this can complicate long-term evolution of data and storage. I’ve seen many issues from customers running multiple Kafka client versions against the same cluster, often very old versions due to constraints in the customer’s environment.

Placing the stitching work server-side, either directly in the primary cluster or in a proxy layer, removes the client complexity and evolution headaches, but at the cost of extra load and complexity server-side. Arguably, we might prefer the complexity to live server-side where it can be better controlled.

3. Integrated vs External Tiering/Materialization Process

Materialization and tiering have some similarities. They both involve copying data from one storage location to another, and possibly from one format to another. Where they diverge is that tiering implies a tight data lifecycle between storage tiers and materialization does not.

For tiering, we need a job that:

Learns the current tiering state from the metadata store.

Reads the data in the source tier.

Potentially converts it to the format of the destination tier (such as from a row-based format to a columnar format).

Writes it to the destination tier.

Updates the associated metadata in the metadata service.

Finally deletes the data in the source tier.

That job could be the responsibility of a primary cluster (that serves reads and writes) or a secondary component whose only responsibility is to perform the tiering. If a secondary component is used, it might be able to directly access the data from its storage location, or may access the data through a higher level API. The same choices exist for materialization.

Which is best? It’s all context dependent. In open-source projects, we typically see all this data management work centralized, hence Kafka brokers taking on this responsibility. In managed (serverless) cloud systems, data management is usually separated into a dedicated data management component, for better scaling and separation of concerns.

4. Direct-access vs API-access

Tiering involves reads and writes to both tiers, whereas materialization requires read access to the primary’s data and write access to the secondary. What kind of access to primary storage and secondary storage is used? Next we’ll look at direct vs API access for reads and writes to both tiers.

Reading from primary storage

We have two types of access:

Direct-access: The tiering/materialization process (whether it be integrated or external) directly reads the primary storage data files.

Example: Kafka brokers read local log segments from the filesystem and write them to the second tier (object storage).

API-access: The tiering/materialization process uses the primary’s API to read the primary’s data.

Example: Tiering/materialization could be the responsibility of a separate component, which reads data via the Kafka API and writes it to the second tier.

Direct access might be more efficient than API-access, but likewise, direct access might be less reliable if the primary performs maintenance operations that change the files while tiering is running. It may be necessary to add coordination to overcome such conflicts.

Reading/writing to secondary storage (materializing/shared tiering)

For both materialization and shared tiering, we must decide how to write data to the secondary system. In the case of a lakehouse, we would likely do it via a lakehouse API such as an Iceberg library (API-access). Shared tiering must also be able to read back tiered data from the secondary system.

A key consideration is that the primary must maintain a mapping of its logical and/or physical model onto the secondary storage. For example, mapping a Kafka topic partition offset range to a given tiered file. The primary needs this in order to be able to download the right tiered files to serve historical reads. But this mapping could also map to the logical model of the secondary system, such as row identifiers of an Iceberg table.

Let’s look at some example strategies of Iceberg shared tiering:

API-Access. The primary uses the Iceberg library to write tiered data and to read tiered data back again. It maintains a mapping of primary logical model to secondary logical model.

Example: Kafka uses the Iceberg library to tier log segments, maps topic partition offset ranges to Iceberg table row identifier ranges. Uses the Iceberg library to read tiered data using predicate clauses.

Hybrid-Access (Write via API, Read via Direct). The primary uses the Iceberg library to tier data but keeps track of the data files (Parquet) it has written, with a mapping of the primary logical model to secondary file storage. To serve historical reads, the primary knows which Parquet files to download directly, rather than using the Iceberg library which may be less efficient.

The direct-access strategy could be problematic for shared tiering as it bypasses the secondary system’s API and abstractions (violating encapsulation leading to potential reliability issues). The biggest issue in the case of lakehouse tiering is that table maintenance might reorganize files and delete the files tracked by the primary. API-access might be preferable unless secondary maintenance can be modified to preserve the original Parquet files (causing data duplication) or have maintenance update the primary on the changes it has made so it can make the necessary mapping changes (adding a coordination component to table maintenance).

Another consideration is that if a custom approach is used, where for example, additional custom metadata files are maintained side-by-side with Iceberg files, then Iceberg table maintenance cannot be used and maintenance itself must be a custom job of the primary.

5. What is responsible for lifecycle management?

We ideally want one canonical source where the data lifecycle is managed. Whether stitching and conversion is done client-side or server-side, we need a metadata/coordination service to give out the necessary metadata that translates the logical data model of the primary to its physical location and layout.

Tiering jobs, whether run as part of a primary cluster or as a separate service, must base their tiering work on the metadata maintained in this central metadata service. Tiering jobs learn of the current tiering state, inspect what new tierable data exists, do the tiering and then commit that work by updating the metadata service again (and deleting the source data). In some cases, the metadata service could even be a well-known location in object storage, with some kind of snapshot or root manifest file (and associated protocol for correctness).

When client-side stitching is performed, clients must learn somehow of the different storage locations of the data it needs. There are two main patterns here:

The clients directly ask the metadata service for this information, and then request the data from whichever storage tier it exists on.

The client simply sends reads to a primary cluster, which will serve either the data (if stored on the local filesystem), or serve metadata (if stored on a separate storage tier).

In the second case, it requires that the primary cluster knows the metadata of tiered data in order to respond with metadata instead of data. This may be readily available if the tiering job runs on the cluster itself. It can also be possible for the cluster to be notified of metadata updates by the metadata component.

6. Schema Management and Evolution

What governs the long-term compatibility of data across different storage services and storage formats?

Is there a canonical logical schema which all other secondary schemas are derived from? Or are primary and secondary schemas managed separately somehow? How are they kept in sync?

What manages the logical schema and how physical storage remains compatible with it?

If direct-access is used to read shared tiered data and maintenance operations periodically reorganize storage, how does the metadata maintained by the primary stay in-sync with secondary storage?

Again, this comes down to coordination between metadata services, the tiering/materialization jobs, maintenance jobs, catalogs and whichever system is stitching the different data sources together (client or server-side). Many abstractions and components may be in play.

Lakehouse formats provide excellent schema evolution features, but these need to be governed tightly with the source system, which may have different schema evolution rules and limitations. When shared tiering is used, the only sane choice is for the shared tiered data to be managed by the primary system, with read-only access to the secondary systems.

7. Shared tiering or materialization?

If we want to expose the primary’s data in a secondary system, should we use shared tiering, or materialization (presumably with internal tiering)? This is an interesting and multi-faceted question. We should consider two principal factors:

Where the stitching/conversion logic lives (client or server).

The pros/cons of shared tiering vs pros/cons of materialization

Factor 1: Client or server-side stitching

When the stitching is client-side, tiering vs materialization may not make a difference. Materialization also requires metadata to be maintained regarding the latest position of the materialization job. A client armed with this metadata can stitch primary and secondary data together as a single logical resource.

We might be using Flink and want to combine real-time Kafka data with historical lakehouse data. Flink sits above the high-level APIs of the two different storage systems. Whether the Kafka and lakehouse data are tightly lifecycle-linked with tiering, or more loosely with materialization is largely unimportant to Flink. It only needs to know the switchover point from batch to streaming.

Factor 2: Weighing the pros and cons

If we want to provide the data in lakehouse format so Spark jobs can slice and dice the data, then either shared tiering or materialization is an option.

Shared tiering might be preferable if reducing storage cost (by avoiding data duplication) is the primary concern. However, other factors are also at play, as explained earlier in The challenges of shared tiering.

Materialization might be preferable if:

The primary and secondary systems have completely different access patterns, such that maintaining two copies of the data, in their respective formats is best. The secondary can organize the data optimized for its own performance and the primary uses internal tiering, maintaining its own optimized copy.

The primary does not want to own the burden of long term management of the secondary storage.

The primary does not have control over the secondary storage (to the point where it cannot fully manage its lifecycle).

Performance and reliability conscious folks prefer to avoid the inherent risks associated with shared tiering, in terms of conversion logic over multiple schemas over time, performance constraints due to data organization limitations etc.

The secondary only really needs a derived dataset. For example, the lakehouse just wants a primary key table rather than an append-only stream, so the materializer performs key-based upserts and deletes as part of the materialization process.

Data duplication avoidance is certainly a key consideration, but by no means always the most important.

Final thoughts

The subject of storage unification (aka data virtualization), is a large and nuanced subject. You can choose to place the virtualization layer predominantly client-side, or server-side, each with their pros and cons. Data tiering or data materialization are both valid options, and can even be combined. Just because the primary system chooses to materialize data in a secondary system does not remove the benefits of internally tiering its own data.

Tiering can come in the form of Internal Tiering or Shared Tiering, where shared tiering is a kind of hybrid that serves both primary and secondary systems. Shared tiering links a single storage layer to both primary and secondary systems, each with its own query patterns, performance needs, and logical data model. This has advantages, such as reducing data duplication, but it also means lifecycle policies, schema changes, and format evolution must be coordinated (and battle tested) so that the underlying storage remains compatible with both primary and secondary systems. With clear ownership by the primary system and disciplined management, these challenges can be manageable. Without them, shared tiering becomes more of a liability rather than an advantage.

While on paper, materialization may seem more work as two different systems must remain consistent, the opposite is more likely to be true. By keeping the canonical data a private concern of the primary data system, it frees the primary from potentially complex and frictionful compatibility work juggling competing concerns and different storage technologies with potentially diverging future evolution. I would like to underline that making consistent copies of data is a long and well understood data science problem.

The urge to simply remove all data copies is understandable, as storage cost is a factor. But there are so many other and often more important factors involved, such as performance constraints, reliability, lifecycle management complexity and so on. But if reducing storage at-rest cost is the main concern, then shared tiering, with its additional complexity may be worth it.

I hope this post has been food for thought. With this conceptual framework, I will be writing in the near future about how various systems in the data infra space perform storage unification work.